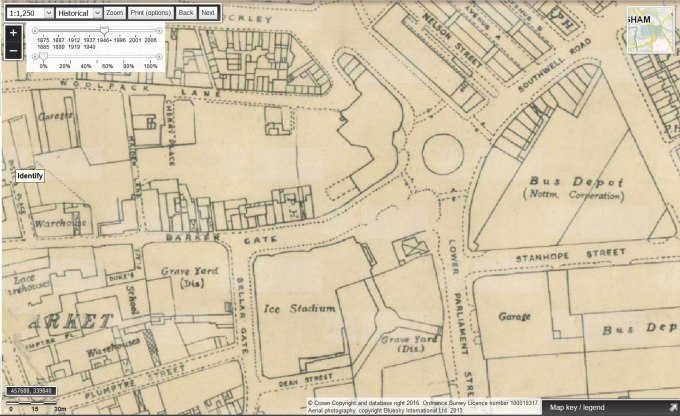

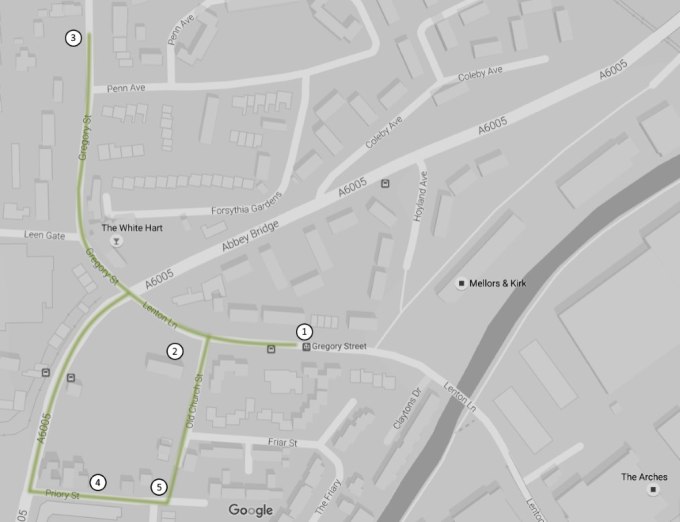

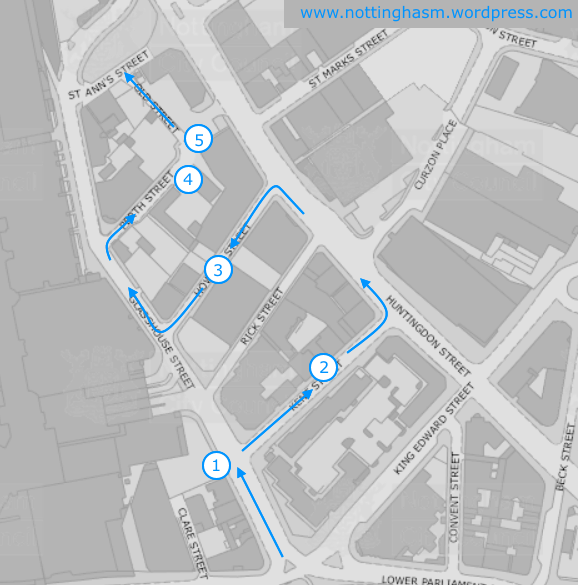

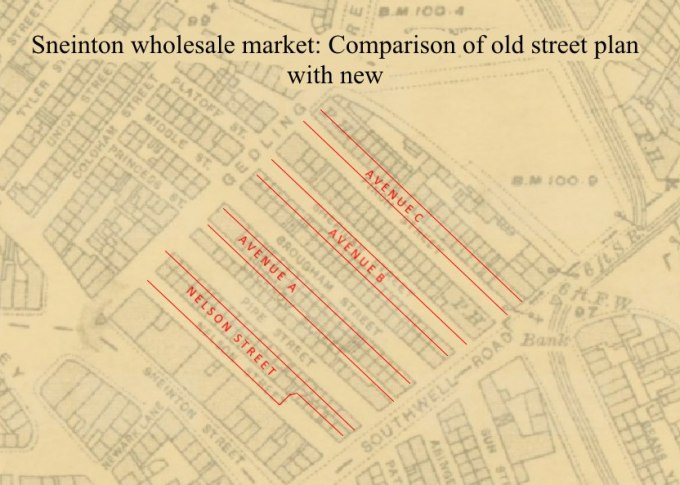

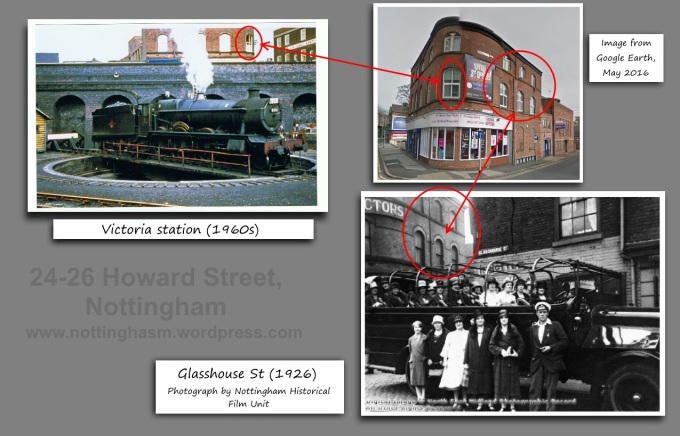

It’s hard to find a lot of in-depth information about Glasshouse Street when researching local history, though it crops-up quite a bit in the supporting cast in other location’s tales. It gets mentioned in relation to ‘The Charlotte Street area’, a slum that used to sit immediately to the west of Glasshouse Street. It’s also heard of in discussions regarding Victoria Station, which replaced the Charlotte Street area. Central Road (later Union Road) and a public footpath passed over the platforms and tracks of the station, connecting Milton Street and Glasshouse Street. The building of the station also diverted Glasshouse Street somewhat, causing it to curve abruptly north-eastwards and connect with Huntingdon Street, when it previously ambled north-west, eventually adjoining York Street (another under-appreciated thoroughfare). It modern times, Glasshouse Street grants access to Victoria Centre’s underground car park, and also hosts a pedestrian entrance to the centre for people approaching from St Ann’s. The modern situation illustrates Glasshouse Street’s problem neatly; you utilise it, but it would rarely be your destination in itself. This situation is a shame, since amateur urban history hunters can find much of interest in and around Glasshouse Street. All of the streets to the east of Glasshouse Street were punctuated with little alleyways and yards, a common feature of poorer Victoria urban areas. Let’s take a short walk beginning at the junction with Lower Parliament Street, to understand the location of such yards.

The southern end of Glasshouse Street is best viewed from the junction of Broad Street and Lower Parliament Street. Look to the right of Glasshouse Street at the brown brick buildings. On this site, and stretching all the way to Convent Street sat a large prison complex also incorporating a police and fire station (1800s-1912). This was replaced by the Empress Picture theatre (1912-1928) and then the Central Market (1928-early 1970s). When Victoria Centre was completed, the traders who occupied Central Market were rehoused within the new complex and the old one demolished. Those that still trade on Victoria Centre’s upper floor are the remnants of the old Central Market community.

The old gas showroom building (43-55 Lower Parliament Street, circa 1920) marks the western side of Glasshouse Street’s southern entrance. It’s hard to imagine a time when simple gas fires aroused enough excitement in the populace that they required such a grand building to showcase them, but apparently this was the case. That building has remained empty and in limbo for many years now, allegedly caught in the bureaucratic vortex of Victoria Centre’s redevelopment. The same can be said of the neighbouring TN Parr buildings. TN Parr was a pork butcher and pie crafter extraordinaire (with three sites around the city centre as well as a base on Lilac Grove in Beeston) who owned the buildings between 1874 and 1928. The Parr family were big players in the pork pie market, since Ken Parr (nephew of TN Parr) started Pork Farms, which TN Parr (the business, not the individual) bought-out in 1969. I like to imagine that Parr family gatherings were somewhat akin to an episode of Dallas, but with pork jelly instead of oil causing tension between different factions.

The wonderful row of buildings has hosted a varied array of businesses over the years, including Broughton Locksmiths in the late 1990s. A peeling sign above one doorway indicates that it was once home to the intriguing-sounding Central Investigation Service, whilst the sign of the neighbouring property shows that it was the Gas Fire Shop. Clearly this part of Nottingham was the place to go for the discerning gas fire enthusiast. I’m sure as a sometimes-inebreated youth in the 1990s I used to stumble into a kebab shop that was part of the buildings. They are boarded-up at the moment, and a notice posted on them last year stated they were due for demolition in April 2015, again as part of Victoria Centre’s redevelopment. I asked owners Intu if I could go inside to make a photographic record of the buildings after glimpsing this sign, and they stated they’d look into it but sadly never got back to me. The Parr buildings seem to have a stay of execution, though, and remain for the time being. You can get a lovely view of their ramshackle rears via Clare Street.

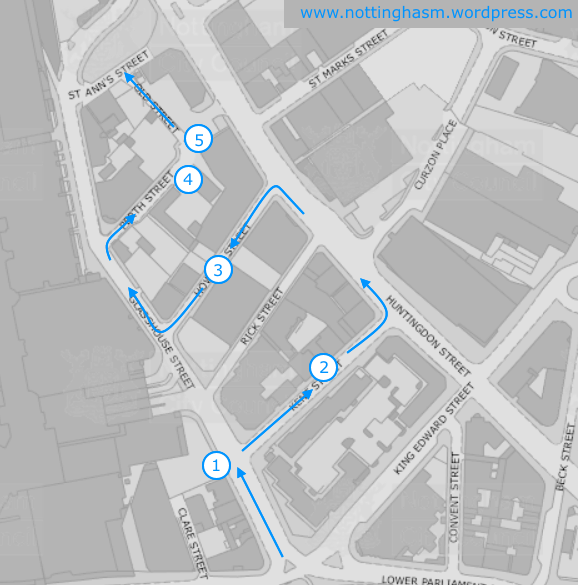

(1) UNION PLACE

On the west side of Glasshouse Street, behind Central Buildings (adjoining the Parr building) once sat Union Place, the first of today’s slum yards. Union Place is mirrored somewhat in the modern space used for deliveries to Argos on Parliament Street, though the old site would have been cramped and overcrowded. Many people seem unaware that you can cut the corner by going across this area and through the little gate onto Clare Street. We’re headed in the opposite direction, though, so turn back around and let’s continue with the tour.

ABOVE: Union Place in the early 1900s. Image from Picture The Past.

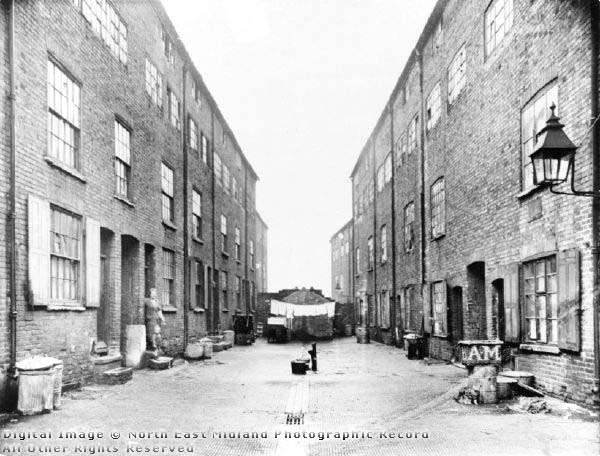

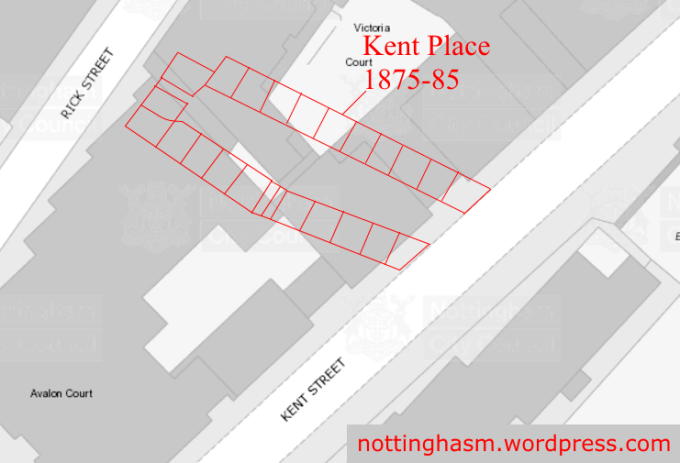

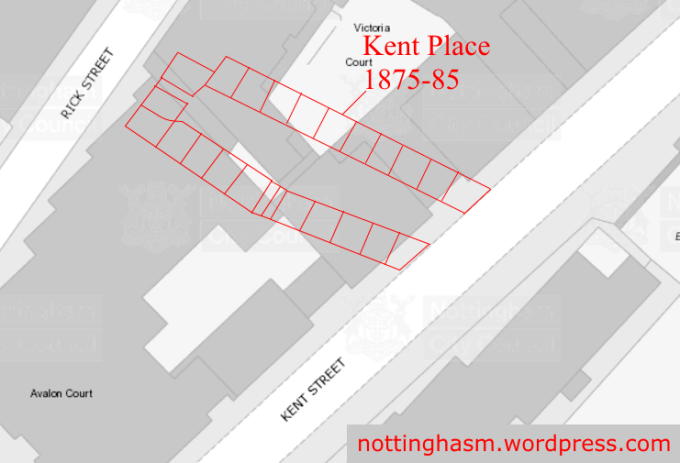

(2) KENT PLACE

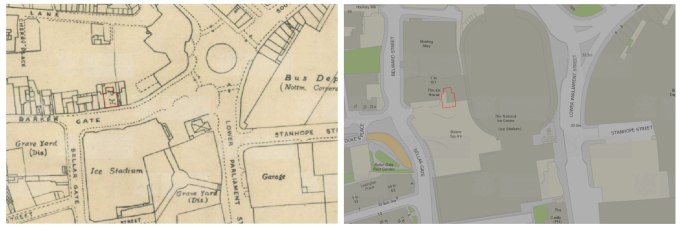

At the junction, turn onto Kent Street, then pause when the entrance to Victoria Court is on you left. Turn back to face north-west, and you’ll be more-or-less looking upon what was once the entrance to Kent Place.

ABOVE: The entrance to Victoria Court in 2016. The entrance to Kent Place overlapped somewhat with this site. BELOW: Kent Place shown in red on a modern map.

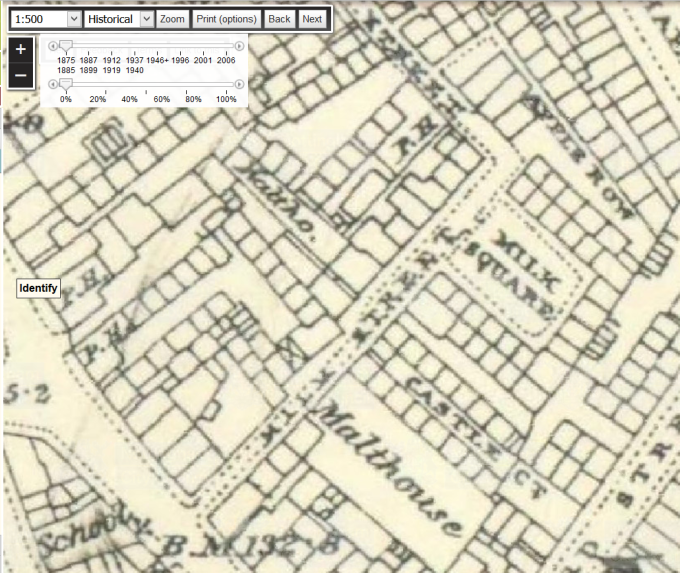

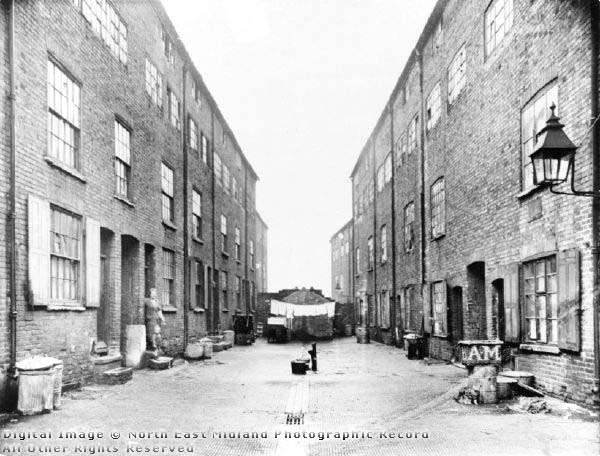

(3) CASTLE COURT

Keep walking west down Kent Street, then take a left onto Huntingdon Street. Keep walking until you spot Howard Street on your left, and walk up this thoroughfare back towards Glasshouse Street. About two thirds of the way up, to your right, is the site that was once the entrance to Castle Court, another of the neighbourhood’s residential yards.

ABOVE: Castle Court around 1932. Image from Picture The Past. BELOW: A map overlay showing the site of Castle Court over a 2016 map.

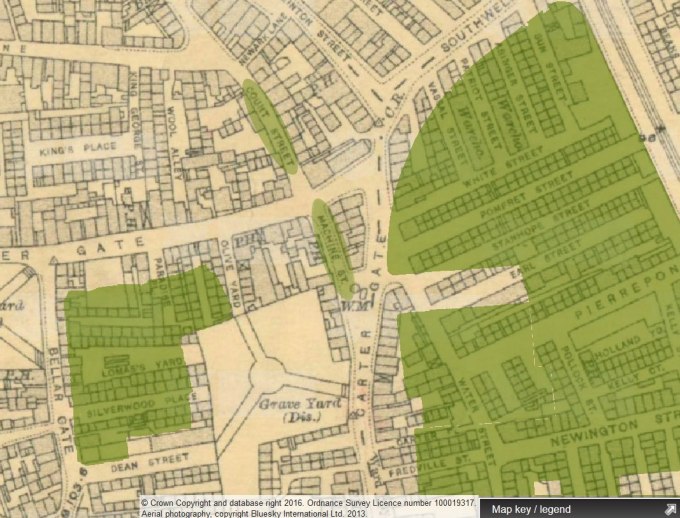

(4) MILK SQUARE

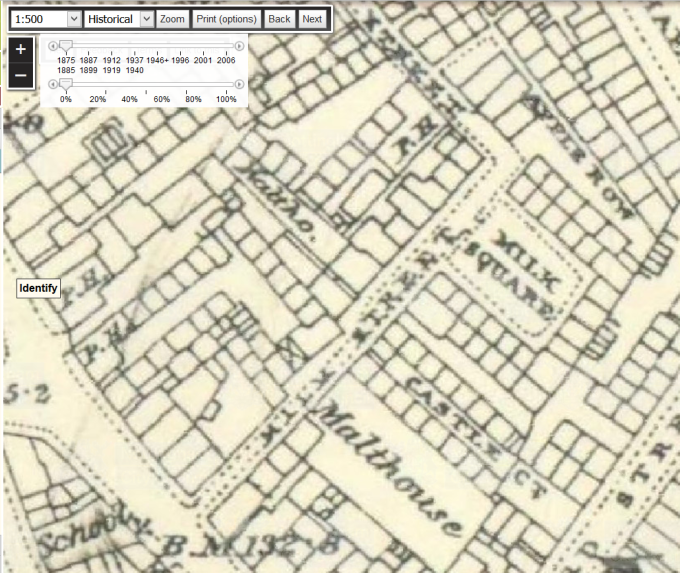

At the top of Howard Street, take a right onto Glasshouse Street then another right onto what is now Perth Street. In days gone by, this was called Milk Street. On your right about a third of the way down would have been the back of Castle Court, and a short distance further (still looking right) was where Milk Square stood.

ABOVE: The Orchestra of Circus Street Hall Men’s Sunday Morning Institute playing in Milk Square for the Sunday School in celebration of the anniversary of the Milk Square Mission. Image from Picture The Past.

(5) APPLE ROW

At the bottom of Perth Street was the entrance to Apple Row. Turn left onto Old Street (which was called Old Street even in Georgian times, so could now possibly be considered Really Old Street), and on your right you’ll be passing the site of an unnamed alley that provided an alternate way in and out of Apple Row.

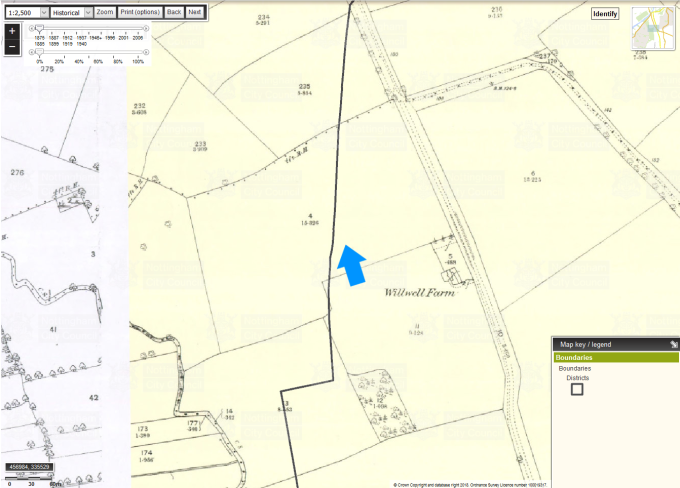

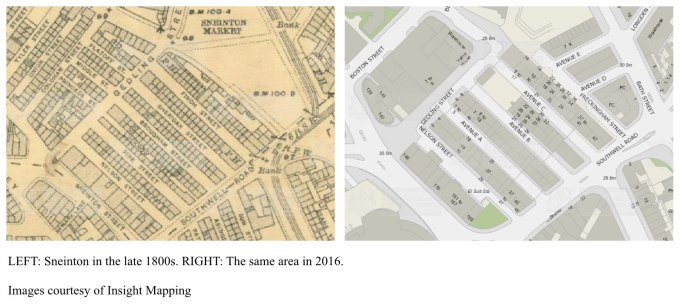

ABOVE: Apple Row circa 1912. BELOW: A close-up of the 1875-85 map from Insight Mapping, showing Milk Street (diagonally through the centre), Castle Court, Milk Square and Apple Row.

On St Ann’s Street, take a left and admire the facade (and — if you’re thirsty — the interior!) of the LGBT-friendly New Forester’s Inn. At the corner of Glasshouse Street, you’ll have a good view of Victorian boozer The White Hart Inn, a pub and hotel. It was renamed The Owd Boots in 1983, when it began to attract a leather-clad rock crowd. The large premises have since been split into separate units, the north-most section trading until recently as a cafe, the middle section as a pub, and the southern portion as a barber. Just south of this building you can see the coach house, stable and hayloft that once serviced the Victorian premises.

This is a very short walk around an area that in days gone by would have been smelly, noisy, and unhygienic. Such locations are lamented, but it’s worth noting that Nottingham would have been unlikely to achieve its prosperity and city status if not for the slum areas. As squalid as they became, such areas housed the thousands who flocked here to work in the booming textiles industry. The workers needed somewhere to live, but let’s not forget that the city’s entrepreneurs desperately needed those workers, too. Without the huddled, slum-dwelling masses to churn-out the lace for them, the businessmen would have had nothing to sell.